It’s been just over a month since we moved into a period when restrictions on social gatherings came into force because of the spread of the COVID-19 virus. 1.5 metres between individuals, no more than two people at an outdoor gathering, no more than five people at a wedding, no more than ten people (including the minister) at a funeral, and certainly no gathering together as a congregation for worship, whether that be as twelve people, or 45 people, or 200 people in one church building.

There is no doubt that this will be an extended period while we need distancing and isolating. There will be weeks, even months, ahead of us in the same mode. We will have plenty of time to reflect on our situation, and to look forward to the time when restrictions are eased and regathering becomes possible.

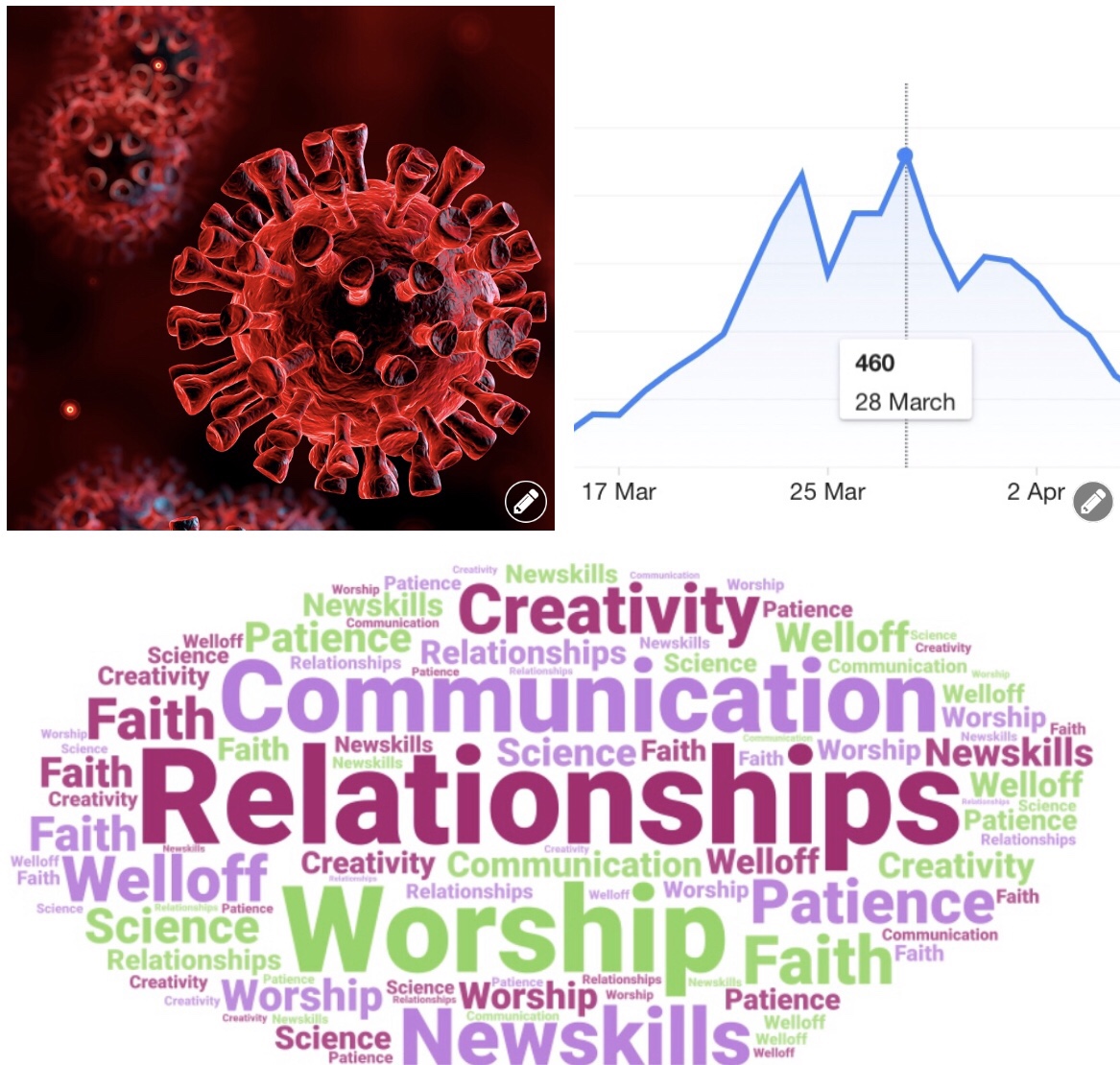

But a month, give or take, is a good time to step back and assess: what have we learnt, during this intense and most unusual period of time? I want to offer some reflections from my own perspective. Here are a handful of things that I have learnt.

1 Relationships are critical.

Human beings are relational creatures. We like to, and need to, relate to other people. Spending far more time in our own homes, and far less time at work or at school, in social outings and family gatherings, is proving to be a challenge.

Social distancing and self isolation are essential to ensure that we minimise, as much as possible, the spread of the COVID-19 virus. But they are challenging to the very core of our being, as humans. Social engagement and interpersonal connections are what we need, and value, in our lives. We need one another. Relationships are critical.

2 Worship is important.

For people of faith, gathering together each Sunday (usually in the morning) is seen as the centre of what it is to be church. Worship is important, but conversation and connection is more important. My home congregation gathers-apart each Sunday, meeting up online via ZOOM, and people are clear that they appreciate the work of our minister (my wife, Elizabeth) each Sunday, in leading prayers, curating musical items, and offering reflections on scripture. Worship is important.

But the group “comes alive” in two moments: at the start, when people recognise others from the Congregation as they join the gathering, and see the faces of their friends appear on the screen; and after worship, during the virtual morning tea, when the conversations really flow. This is where the energy of the group coalesces and builds. Indeed, some congregations have pre-recorded worship which they then follow with live morning tea times, so people can interact over a cuppa. Connection is incredibly important.

3 Good communication is desirable.

We rely on good communication in everyday life. But how good it is depends on the ability to read subtle signs, to see body language and micro signals, to have conversations that ebb and flow in a natural rhythm, like breathing. Online communication diminishes our capacity for subtle communication. It is a blunt instrument.

Being able to see each other on the screen and talk with each other across the ether is very good—but it lacks some critical elements. We can rejoice that we live in an age when we can communicate online across vast distances. Nevertheless we need to recognise how that medium shapes our communications and inhibits deep connection with, and understanding of, one another.

Perhaps we can take this learning on into the post-COVID 19 situation and allow it to inform how we communicate with and relate to others? We need up-close, person-to-person engagement, for good, effective communication to occur.

4 Creativity can flourish under pressure.

I have watched in awe as my various ministerial colleagues have demonstrated great creativity, offering their preaching and praying gifts in new ways. I have read imaginative poems, heard engaging sermons, entered into deep prayer, watched striking short videos, and appreciated the fine photos that have been offered by ministers and pastors, lay preachers and other lay worship leaders, as they nurture their people by creative ways in worship.

Humans are innately creative beings, and creativity can flourish, even (perhaps especially) in pressured situations. Let us hope that this creativity can continue and indeed flourish into the future time, when gathering-together once again will be possible.

5 New skills can be acquired rapidly.

Given the will (and perhaps also the need) to learn new skills, people are capable of fast tracking the process and acquiring new skills very quickly. I have now been told of so many people of mature—very mature—ages, who have taken the challenge, downloaded ZOOM, learnt how to enter a ZOOM meeting, start their video camera, and mute and unmute their speakers—all skills that they never envisaged they could do, just a month or two ago!

What might our churches look like, if we learnt from this? If we took on the challenge to reshape our worship, start fresh expressions of church, adopt new patterns of gathering and sharing and deepening our faith? How might the current experience of individuals learning new skills provide a template for communities setting out on experimental or pioneering pathways? It’s an exciting prospect!

6 Patience is paramount.

In a stay-at-home situation, this is the case; even in a regular situation where we come and go each and every day, patience is at a premium. People who live by themselves are learning a new level of patience, as they wait for fleeting encounters with other people at their front doors, or on the phone, or on the screen.

People who live in families with energetic bundles of energy (children) on hand 24/7 are learning another level of patience, as they isolate together as a family and attempt to conduct the business required to draw a wage and feed a family, even whilst supervising learning-at-home programs. Patience is paramount, in these, and in every, situation that people find themselves at this time.

7 We are well off.

Yes, we are very well off. Indeed, we are very, very, very well off! The great toilet paper panic was an ugly and unsightly episode, but it illustrates how privileged we actually are. At least we have toilet paper to use. Many people don’t. The constant injunctions to wash our hands are important. But we have water on tap (literally) to wash our hands with. Many, many people don’t.

And we have space, the space in our houses and the space on our streets, to practice social distancing. Many, many, many people do not have such space; they live in crowded homes, in overcrowded city areas, where keeping appropriate distance is just not possible. By comparison, it is clear: we are well off.

8 Science is invaluable.

The advances in scientific understanding in recent centuries have enabled us to understand how pandemics (what used to be called plagues) spread. Microbiologists and infectious disease specialists are able to harness their specialised understandings and insights for the benefit of the common good. Medical researchers are able to focus on possible drug treatments, conduct experiments, and produce guidance as to what will assist, and what will not help, as we seek to minimise the spread of the virus.

Science and medicine reporters are doing a fabulous job on the media, providing us with technical insights into how diseases work and how our bodies respond, breaking this information down into understandable bites of information, assuring us of the steps that are being taken to find the vaccine for this virus. We can be grateful for scientific and medical insights.

9 Faith provides a bedrock foundation.

When living in troubled, challenging times, people have regularly turned to some form of faith, for comfort and assurance. We have seen that throughout history. Perhaps that may be happening, these days, when we see the upsurge of interest that has been experienced by churches offering online worship. Many report large “attendances” at online worship, larger than the in person gatherings of past months. It may be too early to tell—but could it be that people are turning to spiritual resources in this time of need?

Certainly, people of faith are active and to the fore, in regular times and now in this unusual time, in ensuring that the vulnerable people in our society are given care and support in these challenging times. I know of many people of faith who are making extra phone calls and offering a compassionate listening ear to people in need.

I know of other people of faith who make home deliveries of food packages to elderly people, or who are staffing food banks operating out of church facilities. Protocols about social distancing are being observed, and needy people are being supported. Looking to the material needs of people in society is important. And in this regard, we clearly see that faith in action undergirds our society. So many people of faith are involved in these kinds of projects. This demonstrates how true religion is (as James writes), “to care for orphans and widows in their distress”.

That’s what I have learnt, this far into the process of social distancing and self isolating. What do you reckon? What are your key learnings?